Paris Art: Real-Life Romantics

Thu 21 Nov 2013

Frida Kahlo and Camille Claudel have a lot in common. Each was a great romantic, a doomed lover and a sensational artist. One married Diego Rivera and the other was loved by Rodin. Work by each is a highlight of this fall’s Paris art scene.

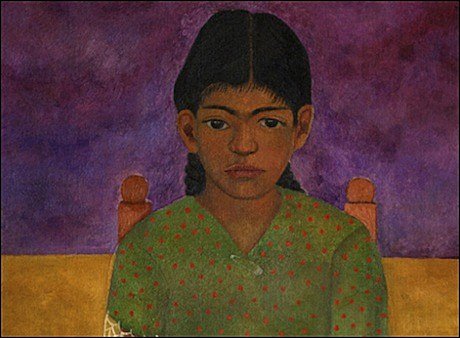

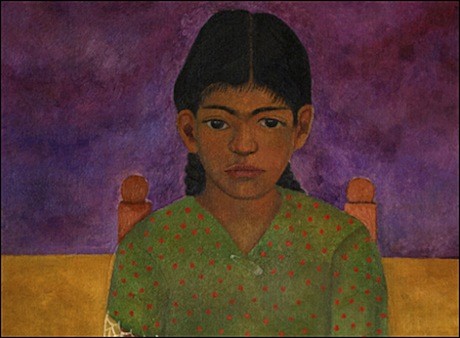

Detail, Self-Portrait, 1926, Frida Kahlo.

Through January 13, Frida Kahlo/Diego Rivera can be seen at the Musée de l’Orangerie and, at Musée Rodin, Camille Claudel is on show until January 5. The two shows have a similar strategy. Each juxtaposes the work of its female artist with that of her older mentor and lover. The juxtapositions work, however. They’re not meant as comparisons—just a way to provide perspective.

Detail, Vertumnus and Pomona, Camille Claudel.

Neither show is exhaustive, but each one illuminates why its heroine is unique. Taken from the Mexican collection of Dolorès Olmedo, the Orangerie has none of Kahlo’s largest paintings. It’s also focused on the couple’s difficult life, with all its operatic dramas. The presentation of Camille Claudel is much smaller and vividly evokes the loss caused by her madness.

If you can make both shows, this is a great opportunity. Work by either artist is both hard to see and well worth chasing. Kahlo’s bittersweet portraits, with their pyrotechnics, are also well balanced by Claudel’s intimate sculptures.

Detail, Sun and Life, 1947, Frida Kahlo.

Although Kahlo’s life was tragic, her art is defiantly rich. The famous self-portraits, with their prominent eyebrows and faint mustache, are as iconic as ever. Claudel, by contrast, can only be glimpsed obliquely. But what’s wrenching about her clutch of works is their poetry. Not only bold in theme and experimental in execution, her sculptures are notable for their humanity. Seeing them next to Rodin’s work only highlights the qualities—and it becomes easy to understand the couple’s mutual attraction.

Detail, The Age of Maturity, Camille Claudel.

The works on view in Camille Claudel came from the artist’s brother Paul and include successes such as Clotho and The Age of Maturity. While both those pieces are impressive, it’s the more intimate works that prove seductive. Chief among these is The Gossips, four seated women engaged in that age-old practice. Like The Wave, it is made in shimmering green onyx.

Detail, The Gossips, Camille Claudel.

In her film Camille Claudel, Isabelle Adjani gave a sense of their maker’s character—how she was a prisoner of her era yet also naturally wayward. As she became disturbed, Claudel destroyed the work she made. But, always insistent on artistic equality, she kept working—always from real nude models. Something few other women artists dared do, this contributed to her mastery of form.

Detail, The Little Mistress of the House, Camille Claudel.

Looking at a work such as Claudel’s The Waltz, however, all these facts simply fall away. What remains with a viewer is simply the rhythm and beauty.

Bear in mind that both women’s work is extremely popular. The Orangerie, especially, has been a victim of “Fridamania.” Many tickets are presold, with visitors sometimes queueing for hours. Busy rooms can also make it hard to see. Reserve your own entry and go prepared for a bit of a wait. That said, there’s no way either show will disappoint.

Detail, Little Virginia, 1925, Frida Kahlo.

• You may want to see Lupe Velez in her one-woman show, Frida Kahlo: Attention, Peinture Fraîche (Frida Kahlo: Watch Out, Wet Paint). Cosponsored by the Orangerie, it runs through January 13 at the historic Théâtre Déjazet. Velez is excellent—I’ve seen it twice—and, if your French is shaky, there are English supertitles.

Did you know there is a treasure trove of content like this in our archives? Register as a friend of the Girls’ Guide to Paris website if you haven’t already, and you’ll have access to all our recommendations and insider info!

Related Links

Frida Kahlo/Diego Rivera

Musée de l’Orangerie

Musée Rodin

Camille Claudel

Lupe Velez

Théâtre Déjazet