The Great Flood of 1910

Sun 24 Jan 2010

© Roger Viollet.

If you saw the film Camille Claudel, with Isabelle Adjani, you know a flood almost drowned the artist in her studio—and Claudel was indeed rescued from her atelier (it was at 19, Quai Bourbon on the Île St.-Louis; the year was 1910). But the Great Paris Flood affected not only Rodin’s ex-mistress—it rendered more than 150,000 Parisians homeless. A quarter of the buildings in Paris were inundated, turning daily life in the city upside down for months. Now, the exhibition “Paris Inondé 1910” offers a fascinating portrait of how the citizens coped.

Those turn-of-the-century Parisians relished their city’s modernity. They were proud of their telephones, elevators, electricity, busy metros and train stations. Plus, they loved la poste pneumatique (an early instant-messaging system able to rocket paper notes through subterranean tubes).

It was all this progress, however, that created catastrophe. A wet summer was followed by heavy snows, saturating the ground itself. When it started raining on January 18, 1910, the Seine rose with unusual speed. Via the city’s system of underground improvements, the water was able to infiltrate sewers, tunnels and underground caves. Soon it was rampaging through the metro and deluging railway stations. Within days, Paris turned into Venice.

Yet this grande crue (great flood) provoked an unexpected unity, and the exhibition shows us how Parisians struggled, improvised—and laughed—together. Amazingly, it’s clear they decided to enjoy the spectacle: “People go to see the floods,” writes one grand lady, “as if they were a revue.”

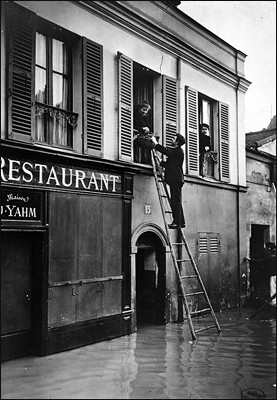

The early newsreels on view are especially dazzling (during my visit, a gang of French children was camped in front of them, pointing and exclaiming). But the whole show features photos of improbable charm. Determined to shop, for instance, women in furs descend homemade ladders into rowboats and gentlemen ogle ladies raising their skirts to totter on makeshift bridges. A crowd in the Jardin des Plantes gawks at a bear—named Martin—escaped from the zoo; a dog refuses to step on a raft and join his fleeing family. Things are desperate, but many in the photos are laughing.

Rue de Seine. © Albert Chevojon and Roger Viollet.

Of course, there are also stunning vistas of half-submerged landmarks. The poet Apollinaire steps out into the street where he lives and compares his neighborhood to “a charming little village in Holland.” Proust is caught grousing about repairs to his parquet floor. Paul Cambon, then French ambassador to London, fumes by letter that he cannot bear to “miss the fun.”

“Say what one will about this Parisian population,” he writes, observing that “nothing can please them but the extraordinary!” Even small ads from newspapers prove he was right. In one, a “gentleman philanthropist” offers “situations for girls and young female victims—all discretion assured.” Even Paris real estate agents refused to admit defeat. (“Ruined by the floods, our vendor sells at a massive reduction and, unlike him, his maison remains untouched by the waters!”)

Of course, Paris inundated was also Paris freezing and Paris paralyzed. “It’s like going back twenty years in time,” sniffs one resident to her neighbor. “No electricity, no elevators, no telephones!” (No public clocks, either; all of them failed at the same moment: 10:50 a.m. on January 21.) Yet, as “Paris Inondé” demonstrates, this was one disaster people faced with panache. Why? Because they were Parisians and they were modern! This irresistible exhibition gives us a real peek at their world.

“Paris Inondé 1910” runs from January 8 to March 28, at Galerie des Bibliothèques:

22, rue Malher, in the 4th Arrondissement, near the St.-Paul metro stop.

Mon–Sun, 1–7 p.m.; Thurs until 9.

Admission: 4 euros (reduced rate: 2 euros).